Open source: what do we think?

Open source: what do we think?

Since the launch of Cal.com, we have received countless messages from founders asking if open-source would be the right direction for their startup to take, and so we wanted to write about the decision-making process of starting cal.com as an open-source company, to help others make a similar decision.

There has been a lot of hype around open source since 2021, and some tech magazines are writing about the "Renaissance of Open Source", but we want to make sure you are doing the right things for the right reasons – or at least reflect on your reasons.

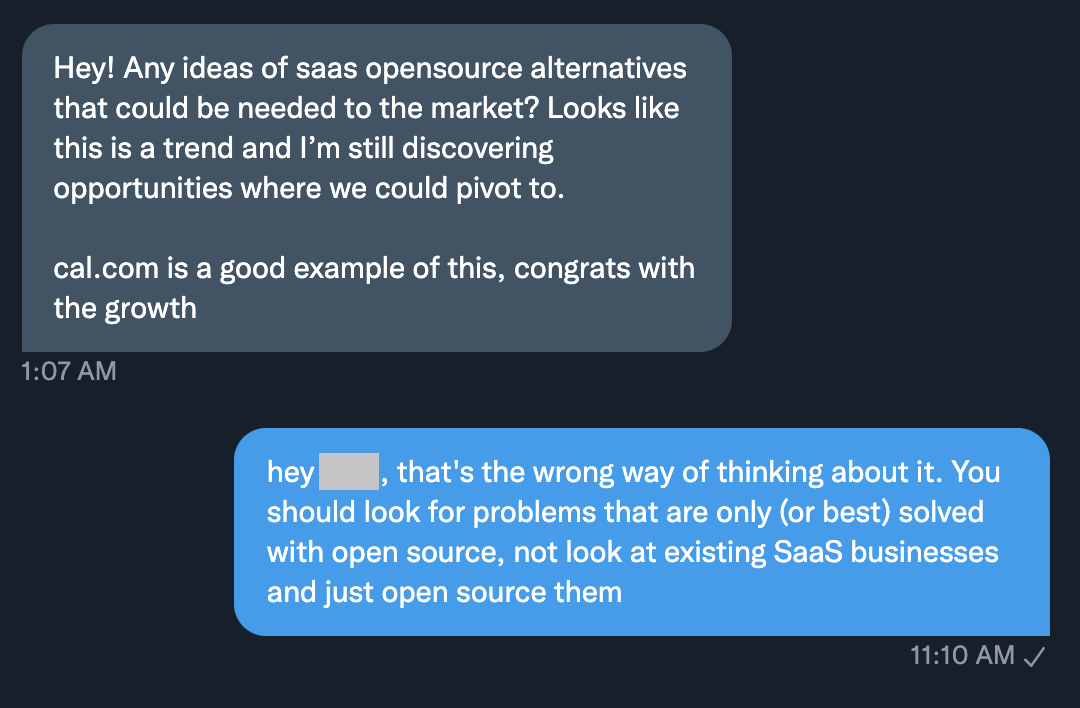

We've been getting similar variations of the question above quite a lot recently (due to the growth and coverage of cal.com), which is why we wanted to write a post outlining how we think about SaaS vs open source and when to open source.

Despite both of us having used many open source projects before and massively appreciated the work they do, neither of would would consider ourselves die-hard open source fans. Cal.com is the first OSS project either of us have worked on, as all of the projects we've worked on before were closed source. Most of the time there was a very good reason those projects were not open source.

Why did we build Cal.com in the first place?

When Peer worked on his previous company, leanhire.com, he found that was in dire need of a more powerful scheduling tool.

Unlike the typical use case where Peer, or his employees, would make bookings (such as in sales or recruiting), they needed a scheduling product for their hiring marketplace. In every two-sided marketplace, your users are interacting with other users, which doesn't fit well with the typical model offered by existing scheduling products.

Scheduling tools like Calendly, SavvyCal, and Motion are amazing products to help you make bookings. However, they do not have the ability to provide the scheduling infrastructure for more advanced scheduling use cases, such as hiring marketplaces, telehealth and more. For instance, it wouldn't be feasible for a hiring marketplace to be paying $19/month for each seat if you have over 5,000 users, like Peer had at Lean Hire.

Existing SaaS scheduling products also don't provide many insights into what's happening inside. In the onboarding for Lean Hire, they previously asked their customers to simply copy/paste their scheduling link and the platform would automatically add it to the outreach emails. However, once the recipient clicked on the scheduling link, the Lean Hire platform didn't have the ability to track what happens next.

They didn't know if or when events happened, and if they were rescheduled or canceled. There was no way to change the booking workflow, design, or API calls that are being made when booking. Hence, an open, accessible, extensible solution that they could self-host was needed.

Peer immediately searched Google for "Calendly open source" because that's what open source stands for: open, accessible, extensible, and self-hostable.

To his surprise, he couldn't find a single project doing what Lean Hire was looking for. Incidentally at this time, hundreds of other people were searching for the exact same thing. Forum threads, Reddit discussions and more were opened by people asking if there was an open-source scheduling product that could rival the most popular SaaS solutions.

Why did we make Cal.com open source?

From the very first day it was obvious to us that Cal.com would be an open-source project. The things we intended to do were fundamentally harder being a closed SaaS product than being open-source.

The key point here is that the limitations of existing scheduling products could only be solved by open-source. A lot of founders go down the wrong path of thinking that they should build an open-source alternative to an existing product, thinking that their product will succeed solely because it's open source. Instead, you should only consider making your project open-source if open-source actually solves the challenges that you want to address (e.g. customisability, self-hosting).

For instance, you could build an open source Twitter alternative, but it's unlikely that it would take off, because social networking doesn't really benefit from being open source. There are many instances of projects which are open source just for the sake of being open source.

However, if you for instance looked at the e-commerce industry, which is mostly dominated by SaaS products like Shopify or BigCommerce, you could see that having an open-source alternative would allow stores to be self-hosted, fully customised and whitelabelled, and extended in ways that are not possible with a closed-source product. This would be a good case of why you should open source your project.

In addition to this, with any open, accessible, and free software, there are obvious and non-obvious drawbacks. Open source has many advantages which you're likely aware of, but open source is not without it's disadvantages.

Monetisation

Commercial open source software (COSS) is a trending model of company where your core product is open source, but you also have commercial offerings which bring in revenue. These types of companies can have incredible growth. It’s the nature of free and open software to have massive adoption early on. Developers love open source. They love to be able to look into the code base, fix simple bugs that may annoy them, or overall just be helpful and give something back. Who doesn’t like to be helpful?

But the massive growth and value creation comes at a cost: value capturing. Pretty much every COSS founder I talk to is thinking about the concept of value creation and value capturing.

A freemium SaaS business has two customers: free tier and paid. And the ratio is usually very good. For example:

“Webflow powers more than 100,000 websites for businesses large and small." – https://webflow.com/customers

Webflow's latest valuation is reported to be $2.1B.

An open-source company, on the other hand, looks fundamentally different, with a ton of self-hosters and free customers, who sometimes don’t even know a commercial company behind the project exists.

For example: WordPress powers over 455 million websites as of 2021, and that number only continues to grow.

“The parent company of WordPress.com, Tumblr, and more, Automattic, announcing a new funding round bringing the company's total valuation to $7.5 billion” – https://cheddar.com/media/automattic-announces-288-million-funding-round

If Webflow would power 455 million websites – or – if WordPress was a centralized SaaS business with the economics and value capture mechanism of Webflow, they would likely be the biggest companies in the world.

Being a COSS startup is essentially playing the long game. You won't capture revenue from people that self-host your product on their own, but you hope that the traction of open source puts you on the radar of big companies that could sign a bigger deal with you.

Hence, thinking about the runway that your company has is important. It will likely take a long time to launch your company, build the product up to a state where it is competitive with closed-source alternatives, then start building traction and finally start to close big deals. This means that if you don't have the funding to keep working on the product whilst it generates little revenue initially, you may not capture enough value to survive.

Contributions

One of the significant benefits of being open source is the contributions from the community. We've had some amazing contributions from the community which we're incredibly grateful for. Some of these are small bug fixes, but others can be huge features.

Usually, if people within a company extend Cal.com for their own needs, for instance to write a Microsoft Exchange integration, they will likely put this code into a pull request so that we can have this functionality inside the project itself.

Most of the engineers on our team were previously people who contributed to the project in their own time, which works great for us because we get to see examples of their work right away, they're already familiar with the codebase, and they already have a passion for working on the project.

Stealing

One of the major downsides of open-source is that with your code freely available on the internet, people will create rip-offs of your product and steal your code.

Despite the fact that we're AGPL licensed and any modifications of the code have to be open sourced, there are still people who do and will continue to violate these licenses. Also, there's nothing from stopping one of our competitors to look into our code and see how we have built features, and then take that code to use in their own closed-source project. If they do a good enough job of it, nobody will know that it was stolen, as their products are closed source.

There's nothing that we can really do to stop this. Hence, we try to tackle the issue of Cal.com rip-offs simply by having a prominent, strong brand. We hope that if someone were to take the Cal.com code and create their own rip-off version, that they wouldn't gain any traction as people know that it's a rip-off, and that the community would report it to us so we can take legal action.

For example, Twitch's source code was compromised in 2021, but if you tried to take their source code and start a rip-off version of Twitch, you wouldn't get anywhere.

So, should I open-source X?

If you are asking this question yourself, you should probably not do it. As we've mentioned above, it is usually very obvious if you need a solution that is open, accessible and extensible or not. If you don’t need it – don’t open source it just for the sake of it.

However, if you want to sell into enterprise, highly regulated industries or just want to build a solution for the sheer masses of people (455M WordPress vs 100,000 Webflow websites) then going open-source makes a ton of sense.

Additionally, make sure you focus on building the best product. The majority of consumers don’t really care if you are open-source or not.

They care about the best value for their money. Open source helps with value creation a ton: the feedback cycle is super fast, community members fix bugs, help with translations, and many other things, but never forget to build a superior product over your SaaS competitor.

Because at the end of the day, that’s all that matters: build something people need.